It started as a minor labor dispute between a studio union and the producers and ended up as the bloodiest labor strike in Hollywood history, and it changed the face of Hollywood forever. It's a story of murder, intrigue, bribery, collusion and Communist baiting. A cast of characters that include corrupt union bosses, movie moguls, gangsters and trade unionists.

To understand the whole story we need to go back to the 1930's. In 1932 an individual by the name of George E. Browne was the business manager of the Chicago stagehands Local 2 of the IATSE. Browne became associated with a man named William Bioff. Together Browne and Bioff were running a little extortion racket. They would extort money from theater and night club owners in exchange for a guarantee of union tranquility. They would promise no strikes and low wage contracts in exchange for cash. This was working fine until the Chicago mobster Frank Nitto (the successor to the Al Capone crime syndicate) got wind of it. Nitto offered Browne and Bioff an offer they couldn't refuse. He would let them live and they would give him two thirds of their profits. It wasn't long before Nitto realized he needed to expand the mobs grip on the entertainment industry beyond Chicago. They needed to go national.

The best way to do this, of course, was to have the IATSE International President in your back pocket. So, the mob made sure that George E. Browne was elected un-opposed as President of the IATSE at the 1934 convention. With an IA constitution that stated the International President must sanction all strikes, (a no strike clause), and having the International President in their pocket, the mob was poised to make their move to Hollywood. Browne and Bioff contacted the heads of all the motion picture producing companies. In exchange for money, Browne and Bioff were to see to it that the wages of the various locals be kept at a comparatively low level and the whole industry was to be kept on a stable and reasonable plan of operation that would be profitable and advantageous to the movie executives. This turned out to be a most profitable arrangement for Browne, Bioff and the Chicago mob, until May 24, 1941 when Browne and Bioff were indicted on federal racketeering charges in New York, where many of the movie moguls maintained their business offices, the two were found guilty on October 30.

Bioff was sentenced to 10 years in prison, Browne to 8 years. Each was fined $20,000. Richard Walsh became the new president of the IATSE at the 1941 convention and he appointed Roy Brewer to handle Hollywood. The arrangement with the producers was basically the same: The moguls put Brewer on the payroll and he and his Chicago thugs guaranteed low wage contracts and no strikes.

Hollywood in the early days had two back lot craft unions. The IATSE had a super local, Local 37, that controlled most of the back lot crafts. When some members of Local 37 (dubbed the “Local 37 White Rats”) launched a rebellion against mob control of the IATSE, the international broke up Local 37 and in 1939 formed four separate locals: Local 44 Propmakers and Set Decorators, Local 80 Grips, Local 727 Laborers, and Local 728.

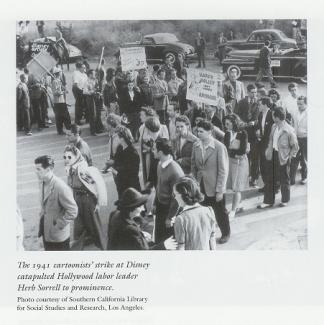

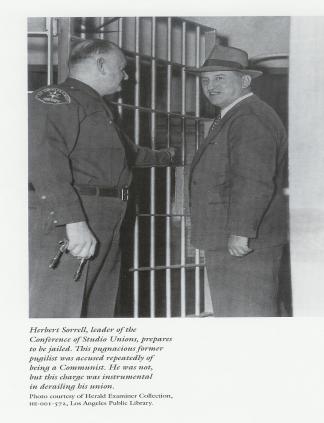

The other studio union was the CSU, the Confederation of Studio Unions. Belonging to the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners international union, they represented the Carpenters, Painters, Cartoonists, and six or seven other crafts. CSU was a model union. Although part of an International Union, the CSU was democratically run by the members with local autonomy and the power to call a strike when necessary. The CSU President was a studio painter named Herb Sorrell. Elevated from the rank and file to the office of president after a successful strike in 1941 for the Cartoonist's, Sorrell often characterized himself as “just a dumb painter.” He was course and gruff and far from dumb, but he was unaware of the corruption and evil that was now lurking back stage.

In 1937 seventy-seven Set Decorators broke away from the IATSE to form their own association, the Society of Motion Picture Interior Decorators (SMPID,) and negotiated an independent contract with the Producers. In 1943 they affiliated with the CSU Local 1421. In November of 1943 Herb Sorrell tried to negotiate a CSU contract that included the SMPID. The producers stalled the contract negotiations for nine months. At that point the IATSE intervened, arguing that the IA had jurisdiction over the Set Decorators. That was all the producers needed, a jurisdictional dispute between two unions. They then stalled for five more months, when Herb Sorrell demanded immediate recognition for his group of set decorators. An arbitrator was appointed by the War Labor Board in February 1945 who ruled that the producers should recognize Local 1421's claim for jurisdiction over the set decorators. The producers refused, even after the set decorators voted that Local 1421 was their proper bargaining agent. The Producer's refusal to bargain is what extended and, in a sense, created the strike of 1945.

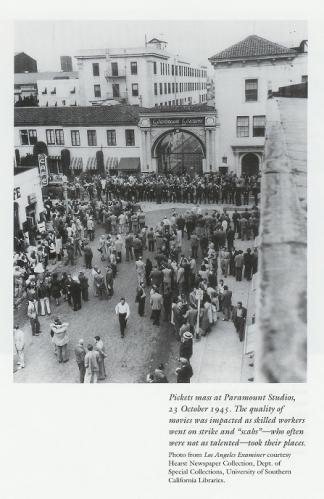

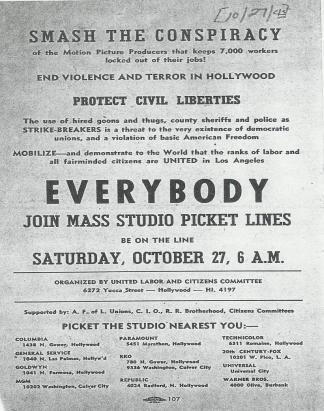

In March of 1945, an estimated 10,500 CSU workers went on strike. They put pickets at all the studios and later started picketing movie theatres also. By that point the studios had 130 films on the shelves - a nine month supply. This was not necessarily the most fortuitous moment for a studio strike. Still, shortly after the strike was launched, Disney, Monogram, and some independents bargained with Local 1421. Columbia, RKO, Universal, Fox and Warner Bros. did not and were affected most severely, with MGM and Paramount right behind.

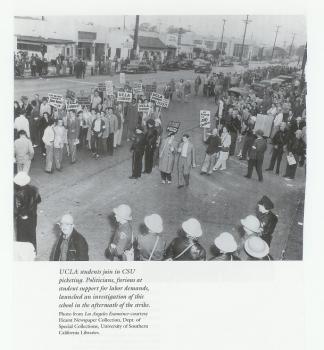

It wasn't long before the strike started to really hurt the producers. RKO was forced by the strike to suspend production on the Selznick epic “Duel in the Sun” staring Gregory Peck, Jennifer Jones, Joseph Cotton, Lillian Gish and Walter Huston. The all star cast refused to work when mass picketing began. Jennifer Jones, leading lady in the $4,000,000 spectacle, walked out when she saw the pickets. Lillian Gish walked past the studio waving to the picketers. Other players including Gregory Peck, Lionel Barrymore, Walter Huston, and Charles Bickford, did not show up at all. The makers of “Night and Day”, the story of Cole Porter, starring Cary Grant and Alexis Smith, failed to do retakes because of the strike. A screen test was also cancelled when Eleanor Parker failed to appear. Aldous Huxley joined Lockheed workers and UCLA students on the CSU picket lines. MGM's location unit of “She Went to the Races” was forced to vacate shooting at Hollywood Park Race Track. Track management was notified the carpenters and building service employees would walk out if the company was allowed to shoot.

John Garfield, Rex Ingram, Dalton Trumbo and John Howard Lawson volunteered to act as observers at the picketing of the studios. They professed to be, “deeply shocked at the violation of American civil liberties in breaking up of picket lines.” At the height of the strike, Peter Lorre shut down “The Verdict”, the last production on the lot. Frightened of the violence but even more of being called a scab, Lorre refused to continue. However, despite the discomfort that stars may have felt about crossing picket lines, movies continued to be made throughout the seven-month strike, and they featured some of Hollywood's biggest stars.

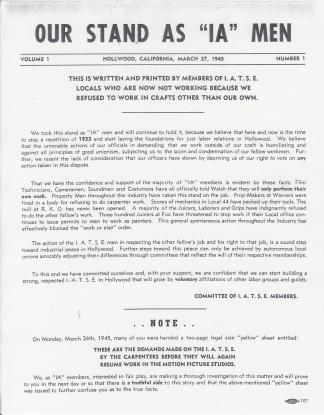

Despite orders from IATSE President Richard Walsh, thousands of IA workers refused to cross picket lines, even in the face of threats of fines and having cards revoked. A rebel meeting of some 1500 IATSE members was held at Hollywood Legion Stadium. The two leaders of the IA rebellion were later suspended from membership. Members of Propmakers, IA Local 44, walked out at Warner Bros. after forty-eight of their members refused to do the work of striking CSU members. Nevertheless, IATSE, in league with the producers, continued seeking to organize its own local of painters and carpenters to replace CSU permanently. That's when it really got ugly.

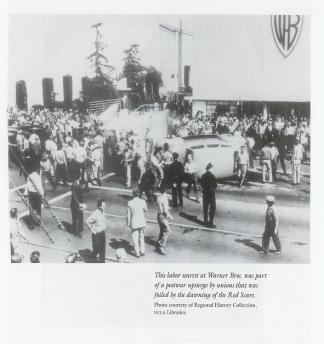

By early October 1945 CSU was not just running out of money, it was running out of patience. Temperatures were at record highs and nerves were frazzled. CSU President, Herb Sorrell, decided to make a stand at Warner Bros. On October 5th, some 300 strikers gather at Warner Bros. main gate at 4 A.M. on a typically warm day during this pivotal month. Shortly thereafter, strikebreakers, Chicago goons and county police attacked. They were armed with chains, bolts, hammers, six inch pipes, brass knuckles, wooden mallets and battery cables. The county sheriffs marched two and three abreast, steel-helmeted and reinforced with tear gas masks, and night sticks, Some carried 30-30 Garrand rifles and two were weighted down with an arsenal of tear gas bombs. The Warner Bros. studio police lobbed canisters of tear-gas from the roofs of the buildings at the entrance.

CSU pickets had their own “white-painted air-raid warden helmets” that shone eerily in the predawn gloom. These helmets and weapons added to the perception that this strike had become a pitched battle, a war. As Sorrell recalled it, “First, they drove through the picket lines at a high rate of speed, several cars. I think we took four people to the hospital. The fire hoses were dragged out; they turned them on the people's feet and just swept them right out from under… they threw tear gas bombs… there were women knocked down… It was a slaughter.” The riot at Warner Bros. hit Hollywood and the nation like a thunderclap.

By the 29th of October the strike was settled. It was “nobody's victory,” said the Los Angeles Times, since many issues were to be fully negotiated over the next thirty days and those not settled were to be arbitrated. “Agreement could have happened in March”, the paper said with exasperation. Perhaps. But their editorial did not acknowledge that the moguls were bent on ousting CSU and they had failed. Hence, the returning CSU strikers could justifiably see their resumption of work as a victory. It was a mixed victory, however. Yes, CSU was to be deemed the bargaining agent for set decorators, but IATSE could still confound the issue by encroaching on the CSU,s jurisdiction over various studio tasks; and a three-person panel was to decide any jurisdictional issues that the two could not work out themselves. The strikers' replacements were to receive severance pay when released and strikers were to return to their jobs. However, IATSE argued, no final determination was made to fire the replacements, only to prevent them from doing the work of the former strikers. The stage had been set for Act Two: driving CSU out of the studios with eager replacements waiting in the wings to take the CSU members' place on stage. As a dress rehearsal for dealing with CSU, the Moguls prevented those IATSE members who had supported the strike from returning to work. They were “locked out,” charged CSU; yet little did the federation know that a similar fate awaited its members in 1946.

To his credit, Sorrell led a union that, relatively speaking, was a model of democratic unionism. In the leading body of CSU were representatives of the various crafts represented in the federation. Meetings at their headquarters at Fifth and Western were frequent and spirited. This was a major reason why CSU could not be underestimated; it had broad-based strength. But organizations are often the lengthened shadows of one individual, and so it was with CSU and Sorrell's dominating presence. Though outsiders charged that Communists dominated the union, this concept was laughable. The Communist foundation in the union movement was within the industrial based CIO, not in the crafts of the AFL, which resisted the idea of socialism and even collectivity. But this plain fact was ignored as the moguls moved to oust CSU from the studios for all time.

It was hard for CSU to focus on structural and strategic change in the industry when the federation was bogged down in jurisdictional contests with the IATSE. These confrontations led directly to a lockout of CSU by the studios in September 1946. A major dispute emerged from the 1945 strike. The conflict concerned whether CSU carpenters or IATSE grips would have control over “set erection.” When the task was awarded to the latter, the stage was set for the liquidation of the former. As a result of the 1945 strike and the subsequent messy working situation, in which the studios had replacements doing CSU functions, a three-man team from the AFL was established to arbitrate disputes. The team consisted of three AFL international vice-presidents: William Doherty, Felix Knight and William Birthright. None of these men had the slightest personal knowledge of the problems involved. None of them knew anything about the industry. They were presidents respectively of a postal workers' union, a barbers' union, and a trainmen's union. The committee was allowed 30 days within which to complete its work. The committee came to Hollywood and held a number of hearings. They visited only one studio - Paramount. That single and sole visit lasted only three or four hours. In December of 1945 the team awarded “all trim and millwork on sets and stages” to the carpenters of the CSU and the “erection of sets on stages” to the IATSE grips. By suggesting that carpenters would control “all trim and millwork” while IATSE would have “erection of sets”, the team injected a new level of complexity in an already complicated workplace.

Obviously there was ambiguity in the phrase “erection of sets.” The word “erection” has two possible and equally valid meanings. They are both given in Webster's dictionary. “To erect” may mean to assemble or build, or it may mean to set erect something that has already been build. Out of this innocent and in itself minor semantic difficulty the IATSE, with close collaboration of the producers, managed to stir up a furious tempest that deprived thousands of CSU workers of jobs they had held for years in the industry, led to months of violent strike, and virtually destroyed democratic trade unionism in the industry.

All construction work of sets on stages had always been done by CSU carpenters. Now Richard Walsh, Browne's successor as head of the IATSE, demanded this work be turned over to the IATSE. The ridiculousness of the demand is evidenced, among other things, by the fact that there did not exist an IATSE local to handle such work. The assembling of sets, constructed by CSU carpenters, had always been done by IATSE grips. Hurriedly Walsh chartered a hitherto entirely unheard of local - a local of “set erectors”. Set erectors were unheard of in Hollywood. The carpenters had always built the scenery and sets. The grips had always assembled them.

The producers, however, immediately acquiesced to Walsh's demand, despite the fact that they knew they were depriving the CSU carpenters of work that they had historically always been theirs, and that this would inevitably cause a major battle.

Naturally the carpenters objected. They continued to work, but under protest, while demanding the meaning of the phrase employed in the three-man directive be clarified. The dispute was carried to the top echelon of the AFL, which finally ordered the three-man committee to explain precisely what it had in mind when it wrote the disputed section of its decision. On August 16, 1946, the committee issued a clarification of the original decision. It established conclusively that the interpretation given to the phrase “erection of sets” by Walsh and the producers was without justification. In the following words the committee explained precisely what the phrase meant: “The word ‘erection’ is construed to mean assemblage of such sets on stages or locations. It is to be clearly understood that the committee recognizes the jurisdiction over construction work on such sets as coming within the purview of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners' jurisdiction.” Walsh and the producers ignored the clarification of August 16. The producers continued to assign construction work to the IATSE. The hypocrisy of the producers thus stands clearly revealed.

Between August 16th and September 20th 1946 the producers and their agents held a number of very hush-hush meetings in Hollywood. Roy Brewer, Hollywood IATSE, attended some of these meetings. Brewer assured the producers that he would supply IATSE men to take the jobs of CSU workers. He promised that should any IATSE men develop scruples about crossing picket lines he would “use the full power of the IATSE to force them to.” He suggested that the producers “put IA men on sets so carpenters and painters will quit…,” and that they “keep procedure quiet so CSU can't gang up at one spot.”

September 23rd was designated as D-day. At a meeting on Friday, September 20th, attended by representatives of Columbia, Goldwyn, MGM, Paramount, RKO, Republic, Fox, Universal, Warner Bros., Roach and Technicolor, a deadline was established: “By 9 a.m. Monday, clear out all carpenters first and then clear out all painters, following which, proceed to take on IA men to do the work.” How were the carpenters and painters to be cleared out? By a simple device. They would be ordered to work on “hot” sets. They could only refuse. Whereupon they would be paid off.

Everything went off on D-day with a smoothness that testified to the care with which preparations had been made. When the men reported for work at MGM on Monday morning, September 23rd, their paychecks had already been made out. Men were taken off their customary jobs and ordered to work on “hot” sets. Construction supervisors, foremen, maintenance men, etc., who had in some cases not done any regular carpenter work for years, were ordered to report for carpenter work on “hot” sets. Even though Twentieth Century Fox attorney Alfred Wright warned the producers at the September 23rd, meeting that “the studios cannot morally or legally assign maintenance men who never have worked as journeymen on sets to set work.”

Thus the carpenters and painters were “cleared out” of the studio. Inevitably the picket lines went up. Inevitably the other CSU members refused to cross the picket lines. The well-laid plans of the smoothly working team of producers and IATSE leaders had borne fruit. They now had their strike. Actually it was a lockout, but by a subtle bit of alchemy they had succeeded in transmuting it into a strike. In any event, called by any name the results were the same; the Conference of Studio Unions, financially weakened by the 1945 strike, had been forced to assume the crushing burden of another major strike. They had no choice. They had either to accept the challenge or meekly surrender and thus acknowledge their inability to defend the rights of their members. By accepting the challenge they risked being destroyed through the slow attrition of a long drawn out struggle against immeasurably more powerful and wealthier opponents. But not to accept it would itself have meant surrender and thus total and immediate destruction.

What followed is history. The history of thousands of men and women, many of whom had invested as much as a quarter of a century of their lives in their studio jobs, thrown out of employment; of these same men and women fighting to save their investment in their jobs, to save their homes, their security, their future; of their picket lines, the only means they had to defend themselves, being forcibly broken; of hundreds of them being rounded up by police and thrown into jail and then obliged to sit weary day after weary day in courtrooms where they were tried like cattle in batches of 20 to 40. To those who sat in the courtrooms and witnessed the proceedings, some of these trials were shocking travesties of justice. In one of them the behavior of the judge was so flagrantly biased that the jury rebelled and acquitted all of the defenders.

During the months that followed D-day, repeated attempts were made by disinterested parties, concerned with the suffering of thousands of workers who had been ousted from their jobs, to bring the opposing sides together to arbitrate their differences. Every proposal of arbitration made encountered an almost invariable pattern of response. Invariably, Herb Sorrell and the CSU accepted without qualification the suggestion of arbitration and agreed to accept the decisions of an arbitrator. Almost invariably the IATSE simply ignored the proposal. Invariably the producers dispatched a piously phrased expression of their solicitude, of their acceptance of the idea of arbitration as offering the only feasible solution, but regretfully concluding that they could not “interfere” (heaven forbid) in a dispute which was not a matter between employer and employee, but solely between unions.

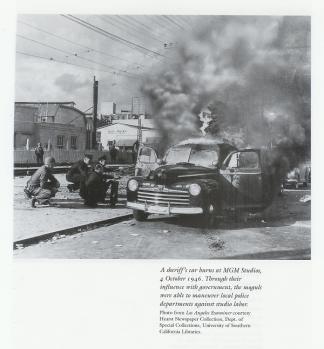

By the second or third week of the lockout, CSU recognized that this was not just a battle to return to the studios - it was a battle for survival. A battle that would rival the “war for Warner Bros.” the year before. A battle that now had reached new heights of bitterness and violence. Sorrell announced that he would “rather not see any women pickets this time.” He warned “there may be men hurt, there may be men killed before this is over but we're in no mood to be pushed around any more!” New picketing tactics were deployed at MGM to block entrances to the studio. Limited to eight pickets in a line at any time, CSU members kept up what was termed a “shuttle” system of picketing, whereby eight were on the line, eight leaving the line and another eight going to the line every minute. This meant the CSU members could amass more pickets while technically not violating the court order limiting its numbers.

Pickets not on the line stalled their cars at the main entrance, blocking the gate for minutes at a time. Still, three buses, driven by studio teamsters, cracked the line with the aid of several hundred law officers. The motorcade's exit was blocked by a sit-down, which delayed departure until officers had arrested twelve of the picketers. Buses were bombarded with bricks and other missiles, causing significant damage. About fifteen people, both pickets and police, were taken to hospitals, suffering from heavy clubbing.

There was open fighting with fists, clubs, stones, and bottles at MGM, involving CSU members, many in WW II uniforms and some wearing battle ribbons, and their opponents. “We fought for our country” one CSU member proclaimed, “now we are fighting for our jobs. Our late president, Franklin D, Roosevelt said this was right.” Some of these uniformed veterans carried a U.S. flag and sang the “Beer Barrel Polka.” Others carried banners calling for “upholding the ideals of Franklin Roosevelt.” “One minute,” said one reporter, “deputies fought demonstrators …the next minute the officers stood at attention as marchers paraded past with the American flag.” The invocation of Roosevelt and the flag was poignant, revealing a perhaps sophomoric faith that elected officers were on CSU's side and not on the side of those who raised funds for their political campaigns. Yet the blows from police batons and the ensuing silence from the White House quickly disabused many about which side the government was on.

A turning point during the lockout came in mid-October when IATSE Local 683 members who worked at film laboratories went on strike in solidarity with CSU. These workers were “very key” said Roy Brewer; “before a set can be torn down they require that they be able to see the set on film.” The workers “shut down” the lab while there were “20 million unprinted negatives in their plant at the time. It was really a crisis,” he sighed. But Brewer was up to the challenge: “we moved in, to take charge of the local.” At the local's office at 6461 Sunset Blvd., preparations were made to resist, including men on the roof twenty-four hours a day. When Brewer and his invaders first arrived at the headquarters, they were met by several dozen husky men with baseball bats. After a heated argument, Brewer and company left. At Technicolor Film Corp., 38 were arrested in a two-hour period shortly after dawn, while an angry throng of 2,000 objected. What happened next was some of the worst violence of the lockout. Five IA members homes were bombed.

The Los Angeles Times editorialized that “Violence had given CSU a ‘black eye'; “bad as the 1945 strike was, the 1946 one was worse for it's element of underhanded terrorism and the State must act,” the paper demanded. The Times worried that mass arrests would be insufficient to halt the picketing since “cases were dismissed both here and in Burbank in wholesale fashion, simply because there were too many off them.” Responding, Governor Earl Warren denounced the violence. Later top CSU leaders were indicted for “criminal conspiracy” as a result of the bombing of IATSE workers' homes.

CSU president Herb Sorrell was enraged. At a meeting of 7,000 members he insisted that the studios were doing the bombings and were the central culprits in the wave of violence. The moguls had imported “known Chicago and Detroit gangsters,” he bellowed. Few were listening, however. The joyous page-one banner headline of a local newspaper, “GOP landslide sweeps nation” was the public's response. A few days later the State responded to this clear electoral message and ignored concerns about the inefficiency of mass arrests when 700 picketers were corralled at Columbia in one of the largest mass arrests ever made in California. After two months of the lockout, more than 1300 had been arrested.

SAG helped organize a conference call on October 24th 1946 featuring Herb Sorrell, Ronald Reagan, Gene Kelly, and the three arbitrators of the December 1945 decision. The purpose was to clarify what the team had meant in its original decision and subsequent August 1946 clarification. Kelly, one of the more consistent progressives in Hollywood, still castigated Sorrell, telling him he was “being shortsighted” - “you are going to risk suicide,” he warned. Sorrell adamantly disagreed, insisting that “if it is a long strike we can exist. We have a lot of backing. There are many members behind CSU. They may be small here but we belong to big internationals. As you know, we can go out and work….We don't have to go to studios to work.”

That evening at 8:30 at Hollywood's Knickerbocker Hotel, SAG met with its erstwhile co-workers from CSU and IATSE. Not surprisingly, it was the “star system” that had brought all of studio labor, including sworn enemies, together. Ronald Reagan wanted the press barred from the gathering since it was “anti-labor.” The still liberal actor was evocative as he remarked, “every one of us here realizes that the one hope for progress and a liberal outlook in America and social gains and social welfare depends on organized labor.” With passion he declared, “right here in this room for the first time is the one thing that the employers have feared most in Hollywood…here is all of labor shoulder to shoulder and side by side exactly the way it should be.” He detailed his extensive meetings with AFL boss William Green - who at one time cried from the stress of it all. The pair met with the three arbitrators whose December 1945 decision awarding “set erection” to IATSE had set the current uproar in motion. Amazingly, with Sorrell sitting in the meeting, Edward Arnold declared that William Hutcheson president of the carpenters international union had proposed accepting the December 1945 decision if Walsh of IATSE “would help…clean out Sorrell from Hollywood.” Reagan also reflected IATSE's viewpoint when he argued that at one time or another all studio unions had scabbed, so why simply act as if IATSE were the sole transgressor?

The CSU leader typically declared once again, “I'm just a dumb painter from Hollywood.” Truthfully, he added, “I go off salary when the men go off. I am not one of those stuffed shirts that sit back and draws pay while my men work half time and picket half time, and get by in that way… Pretty soon I have to borrow money to live.” But he was a painter and like his men, he could still work in the construction industry - California was in the midst of one of its periodic building booms. Thus, the painters were in no hurry to return to the studios without a valid contract. Future Republican senator George Murphy of SAG objected. Maybe painters could work somewhere else but “actors can't work on the outside.” Reagan tellingly agreed: “I am one of those that if people get the idea and stay away from the box office, I may find myself out of work.” However, the future U.S. President seemed angrier at CSU than those who had control over his livelihood. “ I know I have made a lot of enemies…I have had to have guards for my kids because I got telephone warnings about what would happen to me.” continued the charming actor, “I don't know where the telephone calls came from.” Turning to Sorrell, he declared, “I know I took them seriously and I have been looking over my shoulder when I go down the street.” In case Sorrell failed to grasp his intimation that CSU was threatening him, Reagan told him directly, “You do not want peace in the motion picture industry.”

The dumbfounded Sorrell quickly replied, “Nobody is threatened more than I am. My telephone rings all day long.” He not only had to deal with gangsters threatening him but also moguls who had undue influence on fellow labor leaders. The studios, he continued, called the three arbitrators who made the December 1945 decision and “told them what to do.” Regaining his thread of thought, he told Reagan, “Some of you I like very much, including you, Ronnie, and I was very much surprised at that outburst.” Gene Kelly interjected forcefully, If Mr. Reagan attacks Mr. Sorrell, I want it understood that is not the official feeling of this body.”

The most surprising thing about the evening meeting was that even as midnight approached, the attendees were still discussing things amiably - and with no overt red-baiting. Admittedly, this occurred before the November 1946 election, which firmly indicated a new departure in U.S. politics.

Finally, at 1:30 A. M. the meeting adjourned. Matty Mattison of CSU thanked SAG, “particularly…Miss [Anne] Revere, and Gene Kelly and John Garfield. I think they kind of steered us in the right direction tonight.” This event was the high watermark for union cooperation in Hollywood; soon thereafter red-baiting accelerated with breathtaking speed, and purges became virtually compulsory.

As time passed, for example, the mood within SAG changed. President Robert Montgomery was told by one of his Beverly Hills members that the Guild could “live, I'm quite sure, without them, let us see if they can live without us. I'm quite sure carpenters, painters and set decorators will be thoroughly helpless without someone to act in their sets.”

This unforgiving mood had not yet completely blanketed SAG when a special December 1946 meeting was called by 350 of the guild's “Class A members,.” Reagan, who described himself here as a “New Deal Democrat,” spoke fluently, impressing some with his acumen, if not his articulation. Even Edward G. Robinson “absolutely marveled at [Regan's] clear and sequential presentation.” Reagan did not, however, impress Hume Cronyon, who spoke against the future president's viewpoint, which was no less favorable to CSU. Paul Henried was concerned that “a great many of our fellow actors have become innocent victims of this strike…Quite a number of actors have been unemployed for that reason.” Alexander Knox was worried about the quality of the films that were being made: “Scripts are being rewritten to eliminate large sets. This also eliminated small parts….Studios are cutting down their list of [contract] players. Some jurisdictional fights had lasted 40 years,” he mused, “if we wait that long Van Johnson will be playing the parts now played by Mr. Lionel Barrymore.” If CSU was broken, then SAG would be bruised, he counseled. This meeting, which began at 8:30 in the evening, lasted almost four hours. Again, there was hardly any red-baiting. Reagan and Knox were clearly the most effective speakers, and even the former was not that hostile to CSU. Adolph Menjou, who became a premier anticommunist, made the motion to support the SAG board, which was amended to include a call for negotiations between CSU and the studios; the motion passed. Considering that the moguls had sworn off talking to CSU, this vote could be deemed a victory for Sorrell - and a victory for pro-CSU forces within SAG. What was striking about this meeting was that as late as mid-December 1946, anticommunism was not as hegemonic in Hollywood as it was to become a few months later.

What had happened in between to change the environment so decisively? The hearings on Taft-Hartley legislation had sent a clear signal that militant trade unionism would henceforth be viewed as equivalent to Communism. Momentum gathered for a blacklist of those unwilling to observe this edict. Then came the coup de grace: the smashing of CSU. Whatever pro-CSU sentiment existed in the upper echelons of SAG withered in the heat of the post-election offensive against real and imagined Reds. Reagan, who later claimed - falsely - that he was a fierce antagonist of CSU in 1946, became exactly that by the time of the blacklist in 1947.

By the time Congress came to Hollywood in 1947 to investigate jurisdictional disputes, Reagan had no praise for the CSU. On the other hand, he had not expressed the relentless anti-communism that marked a good deal of his public life. He did, however, exhibit tendencies that marked his presidency: though he had impressed even opponents like Edward G. Robinson with his fluent presentations, at the hearings Reagan seemed confused. However, he almost seemed to use this confusion as a tactic: he had converted bafflement into an art form. Reagan, who had been intimately involved in the CSU and IATSE's negotiations with the studios, suddenly had lapses of memory. Roy Brewer of IATSE dramatically informed the House Un-American Activities Committee that the disturbances in Hollywood were caused “by Communists”; that the 1945 decision by NLRB on CSU was “evidence of Communist influence.”

Sorrell was still upbeat. CSU was “in much better condition” in mid December 1946 after eighty-eight days than after a comparable period during the 1945 strike. “Scarcely any prints are being made at all,” he insisted, due to the “splendid support” of Local 683 of IATSE. Box office had “dropped 15 per cent.” “Hal Roach deserted the Motion Picture Producers Association,” CSU said, “because it is reported he completely disapproves of the labor policy.”

The studios, however, were not exactly hurting. In 1947 Fox, a key participant in the lockout, revealed a net profit of $22.6 million for 1946, almost double that of the previous year's profit of $12.74 million. Average salaries of executives in the industry amounted to $215,000, while those unlucky enough to be working outside of Hollywood brought home a mere $104,000. Some in the Hollywood suites were garnering almost $1 million in yearly salary. By 1950, profits had been “far higher than anticipated,” This largesse, however, had escaped studio labor. The 1947 wage scales prevailed under contract until October 1951.

By 1947 the CSU was slowly but surely disintegrating . The studios and IATSE combined to form a rival machinists local, leaving CSU machinists on the outside looking in. The CSU lost their electrical workers and Building Service Employees Local 278. CSU Local 1421 in the spring of 1947 moaned, “We are low on funds, members are doing all sorts of unpleasant jobs, sitting in court is anything but fun, assessments are heavy and the cost of living is high…. Are we ready to surrender? Let's be clear about it; that is our only alternative.” Months later the set designers voted to follow the painters and “permit long-unemployed, impoverished members to go back to work even if it involves crossing the 13-month-old picket lines”; this was approved by a vote of 88 - 23. Even Sorrell himself approved. There were still 3,000 workers locked out then, though CSU claimed a figure of 5,000 - with 4,000 more, including quite a few in IATSE Local 683 - out of work for varying periods. There had been a loss of at least $17 million in wages.

The CIO, not the AFL, lent a hand to struggling CSU members. The organization contacted its affiliates in Los Angeles in an effort to find jobs for CSU members who wish to work in CIO industries; CSU and Local 683 of IATSE, CIO leaders said earnestly, had “made a big sacrifice for the progressive union cause in Hollywood.”

The 1947 - 1948 congressional hearings in Hollywood, however, were a more telling signal of what was happening to CSU. Congressman Carroll Kearns, the former railway worker and teacher who chaired the sessions, was friendly with arch CSU supporter, Father George Dunne. However, Kearns quickly became comfortable with the California lifestyle, riding to the hearings in a sleek 1947 Cadillac sedan assigned to him by an MGM limousine dispatcher. Kearns had voted for the Taft-Hartley bill, whose passage was prompted in part by the disorder in Hollywood. By 1948 these hearings became a venue for venting bizarre accusations about Sorrell's alleged Communist Party membership. A metaphor for these sessions was committee counsel Irving McCann's physical assault of AFL attorney Joseph Padway: the spilling over of their heated exchange symbolized the committee's excesses.

By December 1948 the book finally was closed on the lockout, with the levying of fines totaling $9,650 on thirty-two of the picketers and jail sentences for five others. By November 1950 there was no picket line for the first time in almost five years: the United Brotherhood of Carpenters has called off its token picket line it had maintained ever since the so-called jurisdictional fight that started in 1946. Toward the end, Edmond DePatie, a vice president at Warner Bros., recalled that many were feeling sorry for CSU: at times there was only a solitary picket marching resolutely in front of the studio.

The independents and IATSE leaders did not fare well either after the defeat of CSU. By 1950 a lawsuit was alleging that the major studios had sought to pound not only CSU but also the independents like Monogram and Chadwick as well. Four years later Roy Brewer was running against his colleague Richard Walsh to determine who was to head IATSE. Brewer, who went on to work closely with future U.S. president Reagan, spoke of the “almost unanimous dissatisfaction with the Walsh administration.” Astonishingly, he charged that the Walsh administration was too close to employers; worse, Walsh and his team used “terroristic tactics.” Walsh beat back Brewer and maintained his control of the IATSE until he stepped down in 1974. He died in 1992 at the age of ninety-two. By 1956 Sorrell had lost a court case challenging his dismissal as business agent of Local 644 of the painters, for whom he had served from 1937 to 1952. In a sense, this loss marked the official end of CSU. Herb Sorrell died in 1973; his notoriety having faded, he died in virtual obscurity.

Over the years Hollywood has produced several movies sympathetic to the struggle of working people. However, one movie that Hollywood has never produced and probably never will is the story of its own unionization. The “War for Warner Bros.” may be the greatest story never told…. by the studios.

Acknowledgments:

Class Struggle in Hollywood 1930 - 1950

By Gerald Horne

University of Texas Press

Quoted and paraphrased with expressed, written permission of the author.

Hollywood Labor Dispute: A Study in Immorality

By Father George H. Dunne

Conference Publishing Company

Quoted and paraphrased with permission of the publisher.