A national “no” vote on the whole enchilada is a very real possibility. “UPS overplayed their hand,” said Nick Perry, a delivery driver in Columbus, Ohio. Credit: UPS Teamsters United

There are no flashy special effects in Tyler Binder’s 12-minute video, “Why the UPS 2018 contract sucks!”

No stirring soundtrack, no animation, no laugh track. It’s just him and his whiteboard, explaining in plain language how the tentative agreement would affect every group of workers.

But the video went viral. Just two weeks after he uploaded it, it had 90,000 views on Facebook and 50,000 on YouTube.

Binder, a Wisconsin delivery driver, didn’t expect to become a Teamster folk hero. He just wanted to help his fellow union members evaluate the deal that negotiator Denis Taylor is presenting as the best ever.

It’s clear he struck a nerve. The tentative agreement that covers 270,000 UPS workers, released July 10, is unpopular among Teamster activists.

Until that date, Teamsters were told next to nothing about what their negotiators were doing at the table. A few leaders allied with the Teamsters United coalition or the rank-and-file group Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) were even kicked off the bargaining team for allegedly “leaking” union proposals—to the union’s own members.

The previous UPS national agreement in 2013 barely passed a member vote, and member rejections of several of its regional supplements held up the whole thing for almost a year, until President James Hoffa imposed the supplements unilaterally.

This time, a national “no” vote on the whole enchilada is a very real possibility. “UPS overplayed their hand,” said Nick Perry, a TDU International Steering Committee member who delivers packages in Columbus, Ohio. “I think it’s going to go down in flames.”

But a rejection is not assured. Both the corporation and the union tops are launching all-out campaigns to sell the deal, and using the strike possibility as a threat against members.

Amazon Is Why

Why is UPS so eager to get weekend workers? “They’re doing it for Amazon,” said 30-year UPS worker Tom Schlutow. “It’s because USPS and everyone else is delivering packages for Amazon on Saturday and Sunday.

“I understand the business part of it,” he added, “but they could certainly create full-time jobs. They’re a $6 billion company.”

“It’s a race to the bottom,” said Melissa Rakestraw, a Chicago letter carrier for the U.S. Postal Service, which already has two tiers. Full-time carriers like her make up to $30 an hour, while lower-tier carriers—the ones who make Sunday deliveries, at Amazon’s behest—make $16.

“They aren’t guaranteed work hours, but what actually happens is they work many days in a row without days off,” Rakestraw said. “They use them to alleviate the overtime they’d otherwise have to give us.”

Meanwhile Amazon is increasing its own nonunion delivery force, presumably paid even less. “Out on my route I rarely see a UPS driver anymore,” Rakestraw said. “I see tons of the Amazon white vans running around like mad trying to deliver stuff.”

The Postal Workers (APWU), which represents clerks equivalent to some of UPS’s inside workers, also has a two-tier workforce. The union pushed to eliminate the lower tier in its last contract fight—but that effort got shut down by the arbitrator who decided their contract, pointing to UPS part-timers to justify it.

Postal workers, like UPS workers, also face increasing technological surveillance. A handheld scanner tracks a letter carrier’s position at all times. “They say it’s for real-time tracking of packages,” Rakestraw said. “Amazon texts the person to say, ‘Your package has been delivered.’”

But, she said, “someone at the office monitors this. They will call our supervisors and say, ‘What’s going on on x route, this scanner has been sitting there for 15 minutes.’” Workers wonder whether management can also remotely engage the device’s camera or microphone. Like UPS drivers, letter carriers have contract language that forbids discipline based solely on tech data.

The APWU contract expires in September; bargaining recently kicked off. The Letter Carriers contract expires next year.

NEW WEEKEND UNDERCLASS

What’s so bad about this pact? For starters, it would undercut the full-time drivers who deliver packages by allowing UPS to create a second tier of drivers at a much lower wage.

UPS is forecasting $6 billion in profit this year.

Already a vast underclass of low-paid part-timers do much of the inside work—sorting, loading, and unloading parcels. But till now, package delivery jobs have been sacrosanct.

This deal would create new “hybrid drivers,”whose 40 hours a week could be split between delivering packages and working inside a hub. They would work Wednesday-Sunday or Tuesday-Saturday at straight time, without the protection against excessive overtime or the weekend premium pay that full-time drivers get.

While full-time drivers make up to $36 an hour, these hybrid drivers doing the same physically taxing job would max out at $30.

“Most places, you get a premium for working nights and weekends,” Binder said. “This company wants to give you a $7 pay cut?”

UPS would also gain the right to impose a 70-hour work week during the peak holiday season.

Going into bargaining, drivers wanted the contract to solve their major concerns: excessive forced overtime, harassment by supervisors, and technological surveillance. The deal does little to address those problems—except that it’s likely to shift the overtime burden to the cheaper new hires.

In fact, existing drivers won’t even be guaranteed their full 40 hours if there’s not enough work “available.” Drivers are concerned they’ll be laid off on Mondays because the company will have hybrid drivers get a jump on delivering packages on Sundays.

PART-TIME POVERTY PERSISTS

How about the inside workers, overwhelmingly part-timers? Many of them aren’t happy either.

Their major demands were a $15 starting wage, catch-up raises for people who’ve been underpaid for years, and to create 10,000 new full-time inside jobs by combining 20,000 part-time jobs.

Instead the tentative agreement would raise the minimum to $13, with no catch-up raises. People who’ve put in three years would be making the same as new hires. The only way to get to full-time would be to land a job in the new tier of hybrid drivers.

Leaders in Local 344, representing 4,000 UPS workers across Wisconsin, are recommending a “no” vote on the national deal at this point.

It’s the first new UPS contract since Wisconsin’s “right-to-work” law went into effect, which means there’s a risk disgruntled workers will opt out of union membership.

“Now it’s going to be our responsibility to go get membership cards from every single employee,” Binder said. “It’s going to be a lot easier if we can say, ‘You’re making $15.’”

'VOTE NO' MOVEMENT

The next step is the “two-person meeting” August 9, where two leaders from each union local are expected to vote to recommend the deal. (The deal covering 12,000 UPS Freight workers will also be revealed on that date.) Then it’s members’ turn to vote on the national agreements, along with regional supplements and local riders.

There’s been a lot of water under the bridge since the last UPS contract tussle—including a very close 2016 election for the union’s top seats, where the Teamsters United coalition almost toppled Hoffa. The opposition did especially well among UPS Teamsters, seventy percent of whom voted against Hoffa.

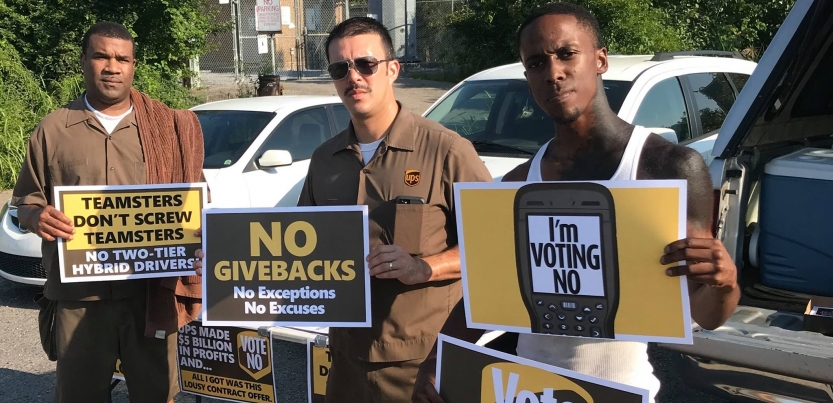

Now TDU activists are leafleting with “10 Reasons To Vote No,” holding parking lot meetings to pore over contract provisions before work, and passing out signs that members post in their car windows with such messages as, “UPS made $5 billion in profits and all I got was this lousy contract offer.”

In New England, the contract passed overwhelmingly last time—but this time, look for big “no” votes, especially at Local 251 in Rhode Island, now led by Teamsters for a Democratic Union-backed reformers, and Local 25 in Boston, headed by joint council leader Sean O’Brien, who recently broke with Hoffa and announced he will team up with Teamsters United’s Fred Zuckerman in the next election.

You can tell UPS is nervous about a no vote. In some of the local supplements, the company is offering ratification incentives, like higher pension contributions, that it says it will withdraw if members don’t approve the deal on a first vote.

But that approach is backfiring too. “It’s kind of a blackmail thing, if you ask me,” said Tom Schlutow, an inside worker in Albany, New York.

“If you let these guys give you ultimatums, what’s the point of having collective bargaining?” said Richard Hooker, a preloader and activist in Philadelphia. “If we let this go down, the company is going to do this every contract from now on.”

START FROM SCRATCH

What happens if members vote no? Both sides return to the negotiating table. Members already voted to authorize a strike, but that doesn’t seem imminent.

When national contracts were rejected by Teamster carhaulers and by Chrysler auto workers in 2015, the union and company bargainers simply resumed negotiations, trying to come up with something workers would approve.

If that happens, this deal will need more than a little tinkering around the edges. The members calling for a no vote say that it falls short in just about every area it covers (or fails to cover).

“They’re going to have to start from scratch,” Hooker said. “But what they need to do is to involve the rank-and-file member more. We pay these guys’ salary. They need to let us know what’s going on—not when they think it’s best, but every step of the way.”