Fresh on the heels of the West Virginia strike, Oklahoma teachers in April led their own nine-day statewide walkout.

Just the threat of a walkout got the legislature to approve teacher raises averaging $6,000. But educators were demanding more, to address decades of cuts.

But in Oklahoma—unlike West Virginia—when state union leaders called members back to school, teachers returned, even though the legislature had budged no further.

Teachers and education unions had been pressing lawmakers for years to increase funding for public schools, but made little headway. Inspired by the uprising that has inflamed West Virginia and other states this spring, Oklahoma teachers formed Facebook groups like “Oklahoma Teacher Walkout—The Time Is Now!” and started to push for a statewide strike.

The Oklahoma Education Association, the largest statewide union, at first set a late-April deadline, but teachers pushed to move up their strike date two weeks, to April 2, to line up with standardized testing dates.

Superintendents throughout the state supported the walkout by closing schools.

A BLEAK PICTURE

Oklahoma teachers’ average pay ranks dead last among the 50 states—and they haven’t had a raise in 10 years. State funding per student has declined 28 percent since 2008, says the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.

In photos shared on social media and with the press, teachers revealed the consequences of underfunding: broken chairs and desks and tattered textbooks listing George W. Bush as the current president. Teachers shared stories of working two, three, or even four jobs to pay their bills.

The unions demanded raises of $10,000 for teachers and $5,000 for support staff. They also pushed for $200 million for classroom funds for more staff, new textbooks, and building repairs.

For over a decade Oklahoma has lost an estimated $350 million each year thanks to tax cuts. Twenty percent of districts have reduced the school week to just four days, shuttering schools on Fridays. Statewide, schools are making do with larger classes, fewer resources, and less experienced teachers, many of them with emergency certifications and little or no classroom experience.

“Right now teachers can only fund creative activities for their classes if they start GoFundMe pages. They can only do labs if the teachers beat the bushes for money,” said Tulsa Classroom Teachers Association President Patti Ferguson-Palmer.

Oklahoma is known among educators as a “dustbowl of the mind,” says Ferguson-Palmer.

“We are losing all these great minds to other states,” she said. “We’ve had more cuts to public schools than anywhere in the nation.”

Organizing for the walkouts was a kind of awakening, especially for newer teachers who weren’t around before the devastating cuts. “Now we know we can have more,” said Aaron Baker, a history teacher in the Mid Del district outside Oklahoma City. “We deserve to be fully staffed.”

CAPITOL PROTESTS

On the eve of the April 2 walkout, the Oklahoma legislature passed a $2.9 billion education budget, with average raises of $6,000 for teachers and $1,250 for school employees.

But teachers and their statewide unions—the NEA affiliate represents most districts, but Oklahoma City teachers are in the AFT—held out for their full demands.

For nine days, a majority of Oklahoma’s students were out of school. Each day, thousands of teachers protested outside the capitol and packed the capitol inside, pushing legislators to raise taxes to fund their demands.

Stephanie Price, a speech therapist in the Moore district, was at the capital almost every day. “The sense of community was really amazing,” she said. “I did get to meet teachers from all over, face to face, standing in line talking about common interests.”

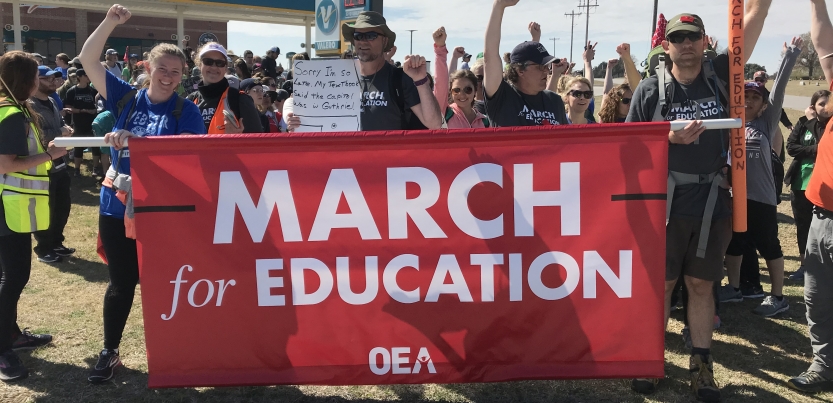

The Tulsa local organized a seven-day march to the capital; 700 people joined for at least part of the 100-mile trek.

Teachers held onto the funding they were promised heading into the walkout. But after nine days, they still hadn’t been able to pressure the Republican-dominated state legislature to line up the 75 percent vote needed for additional tax increases.

That’s when the Oklahoma Education Association announced the walkout would end, and that the union’s next strategy would be to get out the vote for new legislators who would prioritize education funding.

CANDIDATE SURGE

It’s unclear whether continuing the strike would have moved more legislators to fund the teachers’ demands.

But some participants were upset about the strike’s abrupt ending. “Members felt like our voice was not heard,” Lori Burris, president of the OEA’s Mid Del local. “We were not asked. That’s what angered people.”

One silver lining in Oklahoma is that a record 794 candidates have filed for state and federal offices this year, including 30 OEA members. Long lines formed during the protests as people waited to file, challenging legislators who are accustomed to running unopposed.

“People that I didn’t identify as leaders or ready to organize, they just jumped out of their seats and hit the ground running,” Baker said. “We’ve taken people who didn’t consider themselves political at all, and now they are making appointments with legislators and having conversations.”

UP NEXT

What gains the teachers did make are still precarious. While legislators passed mostly regressive sales taxes to pay for raises—including a cigarette tax and a casino tax—they did also levy a sizable amount ($158 million) in taxes on the oil and gas industries.

Republican activists are already gathering signatures for a ballot measure to halt these tax increases. They only need 40,000 signatures to put it on the ballot.

Meanwhile, back at work, Oklahoma educators are still grappling with the same challenge as other educators around the country: how to build enough power and create enough leverage to move statehouses to reverse the disinvestment in public education.

“In order to have an impact you have to be clear about your demands and you have to be clear you aren’t going anywhere,” Price said. “We weren’t enough of an inconvenience for them.”

Teachers have been activated in an unprecedented way, so the question is where to channel that energy. “If I called a general membership meeting four months ago, I’d be lucky to have 20 people,” Burris said. “Now it would be standing room only and they’d all have something to say.”